The word “scribe” can mean a lot of things to us today. For most, we imagine some man, probably with a long beard, hunched over a dimly-lit desk, surrounded by musty books, dipping his quill in some ink and carefully copying a manuscript. And that image is not totally incorrect. Since the inception of written language (circa 4th millenium BCE in ancient Sumer), scribes have been recording, copying, transcribing, and “publishing.”

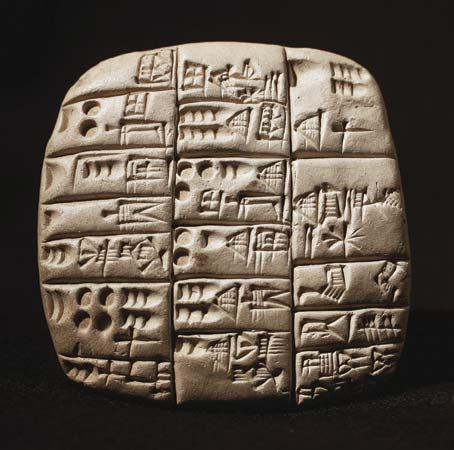

While most of us are accustomed to the scribe I described above, I wanted to take a moment to talk about what life would have been like for an ancient scribe of cuneiform (pictured above). The “language” of cuneiform is the oldest form of writing known to humanity. It originated as a set of pictographs which eventually came to be understood as proto-alphabetical. In fact, the one of the first “alphabets” discovered was that in Ugarit, a coastal kingdom on the Mediterranean (present day Syria).

Scribal works are fascinating not because of what they wrote but because of who controlled the writings/records: the kings. Even in the time of the Bible, “publishing” any kind of material would have been overseen by a king or some other type of affluent authority. Even the redactions (“edits”) of texts by later scribes/editors would have also been overseen by these people in power. And what types of “documents” were published? Largely economical, actually.

I do not have a figure in front of me, but most of the ancient world’s texts are receipts – copies of transactions, property exchanges, and other types of economical activity within a region or empire. Yes, religious writings played their own role in the King’s Publishing Company, but they were far from the most important texts. Written language appeared because the mental capacity (which was impressive, to be sure) of the ancient peoples could not keep track of all that was happening – especially regarding trade between persons and nations.

Take another look at the image. Those imprints would have been made with a stylus – a thin, wooden and chopstick-like rod with a fashioned edge for making the imprints. Earlier this semester in my Ancient Near East and the Bible course I had the opportunity to try my hand at being a scribe. Unfortunately, the results were so bad that I decided to let the sands of time erase my failed clay tablet from human memory. But the exercise had a point: Dr. Nam had us reflect on what it would have been like to be a scribe in the Ancient Near East. How many years would it take to become proficient at this task? How many years would it take to copy whole archives of tablet data, preserving it for future scribes to read and learn from? The answer: a long time. A scribe would have had to practice for many, many years in order to become proficient in this line of work. It truly would have been a lifelong career.

Also consider that the scribes were not self-motivated authors. These were inscriptions that the king (or someone else) was dictating. No one “blogged” back then. No one wrote quick notes to people. Scribal work was incredibly valuable and important; there was not an opportunity to write one’s own thoughts. The onset of private scribal work occurs much later in history.

So take a moment today and realize just how “privileged” we are. Here I am, finishing up this post in a coffee shop, sipping a beverage I do not need on a computer made from glass, sand, and metal to type these words so they can be sent to the “cloud in the sky” for you to read – probably at your leisure. We can publish anything to almost anywhere; we do not need the approval of a king or wealthy patron in order to produce a work of words. And while this has watered down the literary interaction in some circles, it is overwhelming to think about the immense volume of published work over the last two millennia. Think of all the books in all the languages you will never read. Think about all the information you can never know because there is just so much of it.

Be thankful that all of you are scribes – text-ers, tweeters, Facebookers, bloggers, authors, and scholars – and you have the power to influence the world with your words.

I hope we do not mistreat the privilege we have in our ability to write and to share knowledge.